articles

China Elevator Stories

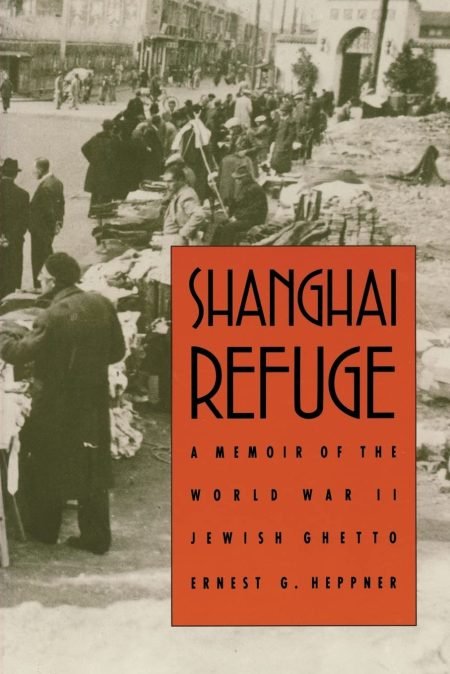

Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War 2 Jewish Ghetto (Chinese History)

Ernest G. Heppner describes the stories of Jews such as him who fled from Germany to Shanghai during World War II in his autobiographical work.

28/09/2024

Ruth Silbermayr

Author

In my opinion, recent happenings in Germany, but also in other countries in Europe, are reminders that what happened during WWII can happen again anytime.

My siblings and me used to visit our maternal grandmother often during childhood and listened to her stories about the war. She had experienced the Nazi-regime, and my grandfather, her husband, had to go to war with many other young men his age. At the end of the war, he was held as a wartime prisoner in a Russian prisoner camp. Just like many men his age, going to war was not a voluntary decision.

Because of my grandmother’s stories and all the movies I was watching as a child growing up in Austria about the Second World War, I am aware of the cruelties and the hardships people had to experience.

I have no Jewish ancestry, but it is said that I have ancestors who belonged to either the group of the Sinti or the Roma. Austrians are often of mixed heritage, and I also have Soviet ancestors, albeit preceding the generation of my grandparents.

My great grandmother was one day found on the doorstep by a family in Austria who took her in as a baby and adopted and raised her as their own child.

While my grandmother liked to talk about what war was like and how she and her family experienced life during the war, and also liked to show us pictures from that period, as well as certificates and letters that were sent from the front, she liked to keep the information of the Sinti and Roma ancestry a secret. Just like Jews, people who belonged to the group of the Sinti and the Roma were persecuted and sent to concentration camps during the Second World War.

Today, historical amnesia has befallen some parts of Europe. Recent events remind us that it’s more important than ever to share stories about what happened during WWII and to be more mindful of history and how it can repeat itself.

One book where the fate of some Jews during WWII is documented is a book called “Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto”, written by Ernest G. Heppner. Heppner was born in 1921 in Breslau, Germany, as the son of Jewish parents.

The book follows his story and the stories of other Jews who could escape Europe and found refuge in Shanghai. His story starts in the prewar period and describes how Jewish people lived among the German population and what they experienced during that time:

“About one month after my fourteenth birthday, on September 15, 1935, additional racial policies were implemented at Nuremberg. Contact between Jews and non-Jews was severely restricted. Jewish doctors and lawyers were no longer permitted to have non-Jews as patients and clients. Most public places such as parks and theaters were put off limits to Jews. (…)

Finally, I was expelled from school, not because of my behavior or lack of academic performance, but school principals had been discouraged at their discretion to expel Jewish students.”

Later, he shares what the Jewish community thought of the current situation:

“The situation was ominous. Hitler’s anti-Semitism was a constant topic of discussion in the Jewish community, and there was no end of speculation as to what could have caused his hatred of Jews. ‘The Jews did not care for any of his paintings’, said some, though ‘His aunt was incorrectly treated by a Jewish physician’ was by far the most popular expression.”

Malignant narcissism has been written about a lot in this decade and the last, but during that time, it hadn’t. People who are familiar with malignant narcissism will know that there could have been an underlying reason that made Hitler hate Jews, but that it could also likely have been because this is simply what a narcissist does: See individuals, groups of people, or people who belong to a different religion, culture or nation as enemies who need to be killed. Often, there is no obvious reason why a narcissist does so.

A lot of high-ranking-members of the NSDAP were certainly malignant narcissists as well. The lack of consciousness, maliciousness and cruelty found in many of these members is what you will usually find in a malignant narcissist.

He goes on to write:

“On November 9, 1938, attempting to make the event appear as a spontaneous outburst by the German people, gangs of Hitler’s Brownshirts, in a well-planned and well-organized operation, went on a rampage. They roamed the streets of the cities in Germany and Austria, and for Jews it became a night of horror. They destroyed Jewish property, looted stores, smashed shop windows, and beat, raped, and murdered Jews. According to the Nuremburg laws sexual intercourse between Aryans and non-Aryans had become illegal; still, like any other ‘crime’, it continued. (…)

The November Pogrom signaled the beginning of the horror for Europe’s Jewry and gave the world a chilling preview of the Holocaust.”

When the Nazis started transporting Jews to concentration camps, to many Jews, it was clear they had to leave the country if they wanted to survive:

It all looked so hopeless. We could not stay in Germany any longer, that was certain. My mother had been corresponding with her niece, Mary Weintraub, who lived with her husband in Washington D.C. Mary had written that she wanted us to leave Germany and to come to the United States.”

The United States had a quota system for Jews who wanted to immigrate, and the quota for that very year had already been filled, so the author. Many other countries had quotas or other requirements and visas that were hard to obtain.

Shanghai was one place that had no visa requirements for Jews. Ernest G. Heppner writes:

“What we heard was not comforting: The Japanese, who were allies of the Nazis, had bombed and razed Chinese cities – especially Nanjing – and had occupied Shanghai since 1937. Furthermore, there was a war raging in coastal areas. There would be no way for us to make a living in Shanghai and no assurance that we would be able to survive there. When we inquired about transportation to Shanghai, we were sternly warned not to attempt to go there. It was suggested that we might be unable to disembark and could be forced to return. What to do?

I had made up my mind not to stay in Germany any longer, and my mother finally decided to ask her old travel agent for advice. China was at the other end of the world: how would one get there? Were there other people besides Chinese living there? Who had ever heard of anyone but criminals going to Shanghai? How would one communicate? The agent reported that one could indeed go to China without restrictions. He confirmed that there were obstacles, and that there was a war raging in the coastal cities. Further, very few passenger ships were going to the Orient, and those – primarily Italian and German ocean liners and a few Japanese steamers – were booked solid for the next six to twelve months. The journey would take about four weeks. Since no one would guarantee that passengers could land in Shanghai, a round-trip ticket would have to be purchased. (…)

Some Jews in Berlin, attempting to get additional information, had visited the Chinese Embassy. They said that they were not told much, except that it was dangerous to enter Shanghai. After crossing a guarded bridge, it was necessary to crawl under barbed wire, and of course, the best time to do that would be at night. Apparently, although the Chinese government had no jurisdiction over the Shanghai International Settlement, it had no interest in encouraging additional foreigners to enter China.

It was insane to go penniless to a strange country in a war zone, leaving family and friends and all belongings behind. But my mother was a resolute, determined woman. Her instinct told her we would be better off abroad, no matter where. (…) The travel agent assisted in preliminary preparations of the detailed paperwork required by the German bureaucracy and contacted the Gestapo to expedite the processing of our documents.

Since my mother had anticipated leaving, she already had most of the voluminous paperwork completed. In the few days left we went to the police headquarters and, together with the other necessary papers, received the all-important Führungszeugnis.”

Ernest G. Heppner goes on to describe the beginning of their journey, which soon started and was filled with dangerous situations, which can be read in his autobiographical book.

They eventually arrived in Shanghai, where he stayed from 1940 to 1944.

“Ernest ended up in Japanese-controlled Shanghai, the only place refugees could land without a visa. There, as a volunteer driving a truck for the British army’s Shanghai Volunteer Force, he got meals and was better off than many other refugees. After Pearl Harbor, in December 1941, conditions among the city’s refugees worsened–American relief funds, the refugees’ lifeline, could not reach Shanghai. In 1943, under pressure from Germany, the Japanese set up a ghetto. Ernest spent two years in the Shanghai ghetto before the city was liberated in 1945. After the war, he worked for the U.S. Air Force in Nanking, China, for several years, and later immigrated to the United States.”

If you want to learn more about Ernest G. Heppner’s life in Shanghai, I highly recommend his book, Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto.

Have you ever heard of Jewish people who emigrated to Shanghai?

Your words have a certain weight to them — they sit with you, long after you’ve finished reading.

Thank you!