articles

China Elevator Stories

Life in China as an Expat

I used to live in China from 2009 to 2010 and from 2012 to 2019.

06/01/2025

Ruth Silbermayr

Author

I lived in China from 2009 to 2010, and from 2012 to 2019, with a few breaks (for the births of my children).

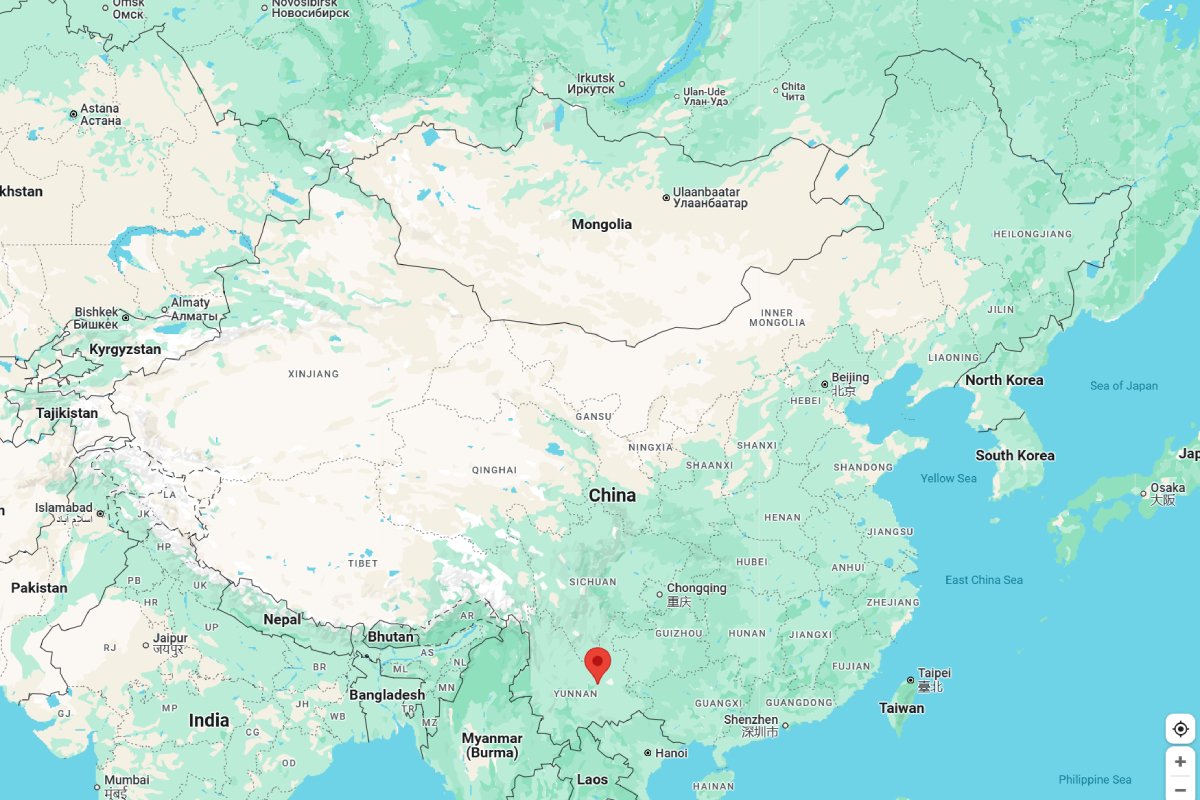

Life in Kunming, Yunnan Province (2009-2010)

From 2009 to 2010, I studied as an exchange student in Kunming. At first, it was hard getting used to life in China. Everything was quite different; things worked in a completely different way. I couldn’t speak Chinese fluently when I first arrived in Kunming, and I found most tasks, such as looking for a flat or registering at the police station, burdensome.

I had heard a lot of good things about Kunming, and that most exchange students who went there really appreciated the city. I didn’t have a good impression of Kunming when I first arrived, but I came to enjoy and appreciate the city later.

It is a big city compared to Austrian standards, and I felt overwhelmed quite a bit. If you’ve never been to China, you may have a similar experience. But once I had stayed for a year, traveled to other areas, gotten to know the city better, and made a few Chinese friends, I found the city enjoyable.

I encountered a few common problems, such as having to give up my apartment and find a new place to live within two weeks. I used to share an apartment with two other exchange students—one man was from India, and the other was from Sweden. Luckily, another exchange student from Switzerland had a free room, and I had no problem finding a new place to live. However, I had to move out of that place as well because, as I later found out, it was an apartment complex for relatives of military personnel, and foreigners weren’t allowed to live there. I found another shared flat where I could rent a room, and I lived with German friends and later with a Chinese friend.

Being thrown out of an apartment is a very common occurrence in China, and it’s always good to have a backup plan, such as saving up enough money to stay at an affordable hotel or hostel in an emergency (if they aren’t booked out, which used to be the case with some hostels in Kunming), or knowing enough other people, such as other expats, who can help you find a room quickly. If you work in China and can afford it, hiring a property agent to look for a flat that is available for immediate rent is another option you can choose.

When I moved to Kunming in 2009, there was no subway and no international shops like H&M. Chinese fashion is often made for an average height of 1.60 meters for women, and women like me, who were 1.70 meters or taller, could have a hard time finding clothes that fit. Today, the city has subways, and getting around is more comfortable than it used to be. International shops are now easy to find, and finding clothes that fit is not as much of a problem.

Yunnan is a province known for its large population of ethnic minorities. Most of my friends in Kunming were not Han Chinese but belonged to other minority groups such as the Bai, Dai, Hui, Naxi, and Yi.

Is Kunming a Safe City to Live In?

Personally, I didn’t encounter any problems when I lived there. Chinese friends often made sure they would accompany us home when we took a cab at night, for example, to ensure we arrived home safely. Some Chinese locals are very friendly, but they also usually warn about corrupt people and criminals, who exist in the city as well. A common problem in Chinese cities can be what is called 黑社会 (“Dark Society” or Mafia-style gangs), some of which are known to act as gangs who steal money from people, while others may be even more criminal.

Once, when I left my apartment in the morning, a sheet of paper had been posted on the wall right next to our entrance, warning people that someone had tried to enter the garage without living in the compound, then threatened the guard at the entrance and stabbed him a few times with a Chinese-style knife. The guard survived and was recovering from his wounds at a hospital. Many compounds in China have guards who monitor who is entering, or only allow people who live in the compound to enter. Often, there is a gate that you can only enter if you have a card that allows access.

A few years later, when I was living in Shenzhen, a particularly terrible attack made the news, called the “2014 Kunming attack.” According to Wikipedia, this is what happened:

“On March 1, 2014, a group of five knife-wielding terrorists attacked passengers at the Kunming Railway Station in Kunming, Yunnan, China, killing 31 people and wounding 143 others. The attackers pulled out long-bladed knives and stabbed and slashed passengers at random. Four assailants were shot to death by police on the spot, and one injured perpetrator was captured. Police announced on March 3 that the six-man, two-woman group had been neutralized after the arrest of three remaining suspects. As of 2024, it is the worst mass stabbing in Chinese history. (…)

On March 3, the Ministry of Public Security announced that police had arrested three suspects and said that an eight-person terrorist group was responsible for the attack, with five direct perpetrators and three others involved only in plotting. The leader of the group was named Abdurehim Kurban, one of the assailants killed on the scene.

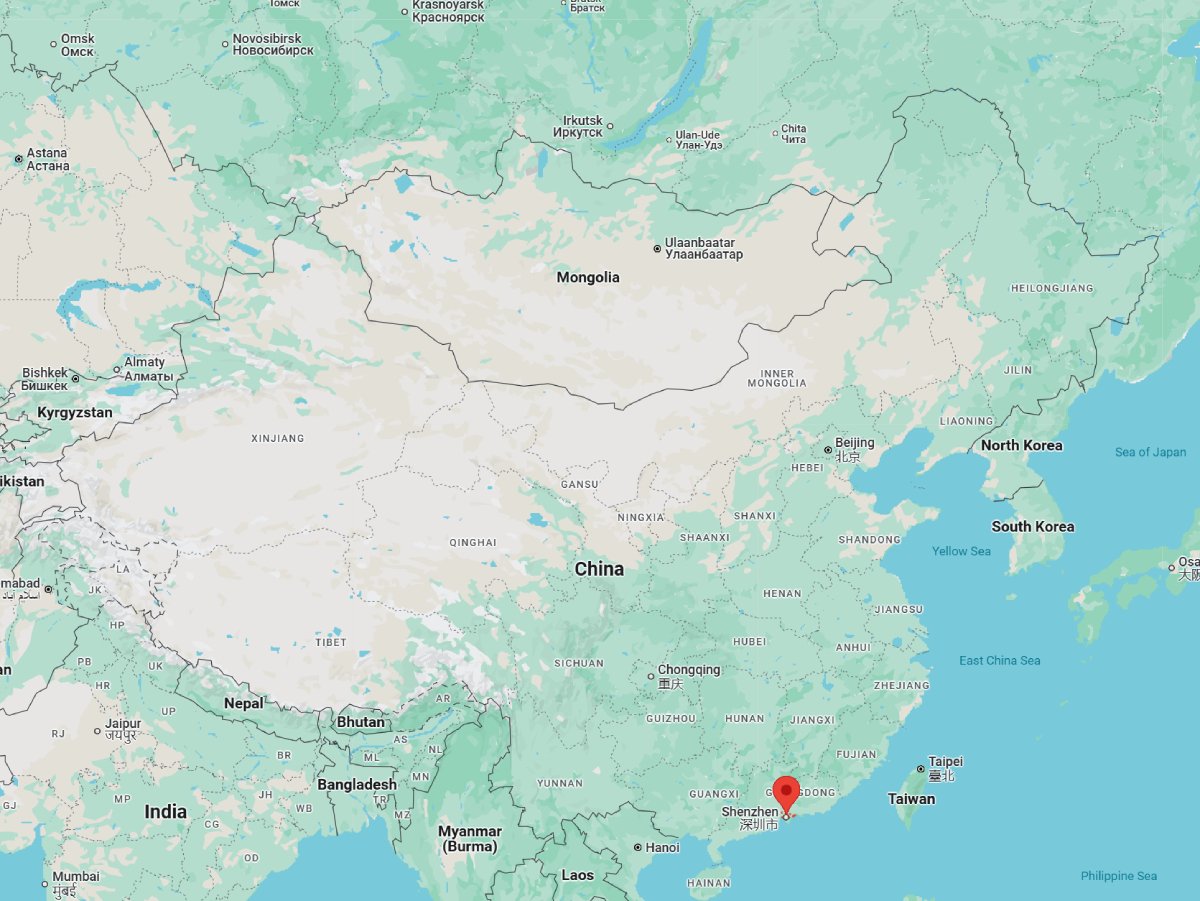

Qin Guangrong said that the captured wounded suspect had confessed to the crime. He asserted the group started off in Yunnan and originally planned to participate in “jihad” abroad. They allegedly tried unsuccessfully to leave the country from southern Yunnan and also from Guangdong. Unable to do so, they returned to Yunnan and carried out the attack.”

The attackers were identified as Uighurs from Xinjiang.

Kunming is the capital of Yunnan province, which shares a border with Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam.

I visited Shangri-la in Northern Yunnan in 2012 and met two former police officers, one of whom had worked in the drug prevention department near the China-Myanmar border. The region bordering Myanmar is commonly known as a popular entry point for drugs from Myanmar into China.

Getting from Yunnan to Laos, and sometimes later to Thailand, is part of a popular escape route for people from various regions and countries, such as North Korea. It is known as part of the escape route that North Korean refugees, who have fled from North Korea to China with the help of human traffickers, take. China tends to send North Korean refugees back to North Korea if discovered, where they face death, which is why these refugees usually try to leave China for other countries. To do so, they must keep themselves hidden and try not to be discovered. Things used to be different. A friend and former co-worker of my former Chinese father-in-law, who used to escape from North Korea to China by swimming across the Yalu River (a few decades ago), has since received Chinese citizenship and established a successful life in Northeast China, integrating very well into Chinese society. His granddaughter attended the same kindergarten class as my younger son. The grandparents passed on North Korean to their children and grandchildren but spoke the local Northeastern Chinese dialect fluently, with no foreign accent, when I met them.

Back to Kunming: During my time living there, I didn’t encounter any dangerous situations. I witnessed a few situations where drunk people became aggressive, but overall, I enjoyed a safe time in Kunming. Many Chinese cities have introduced bag scans at subway and train stations, which scan for weapons such as knives or guns, so citizens can stay relatively safe.

Life in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province (2012-2014)

I have written about my life in Shenzhen on my blog, which I started after moving there in 2012, and I didn’t encounter any dangerous or life-threatening situations there.

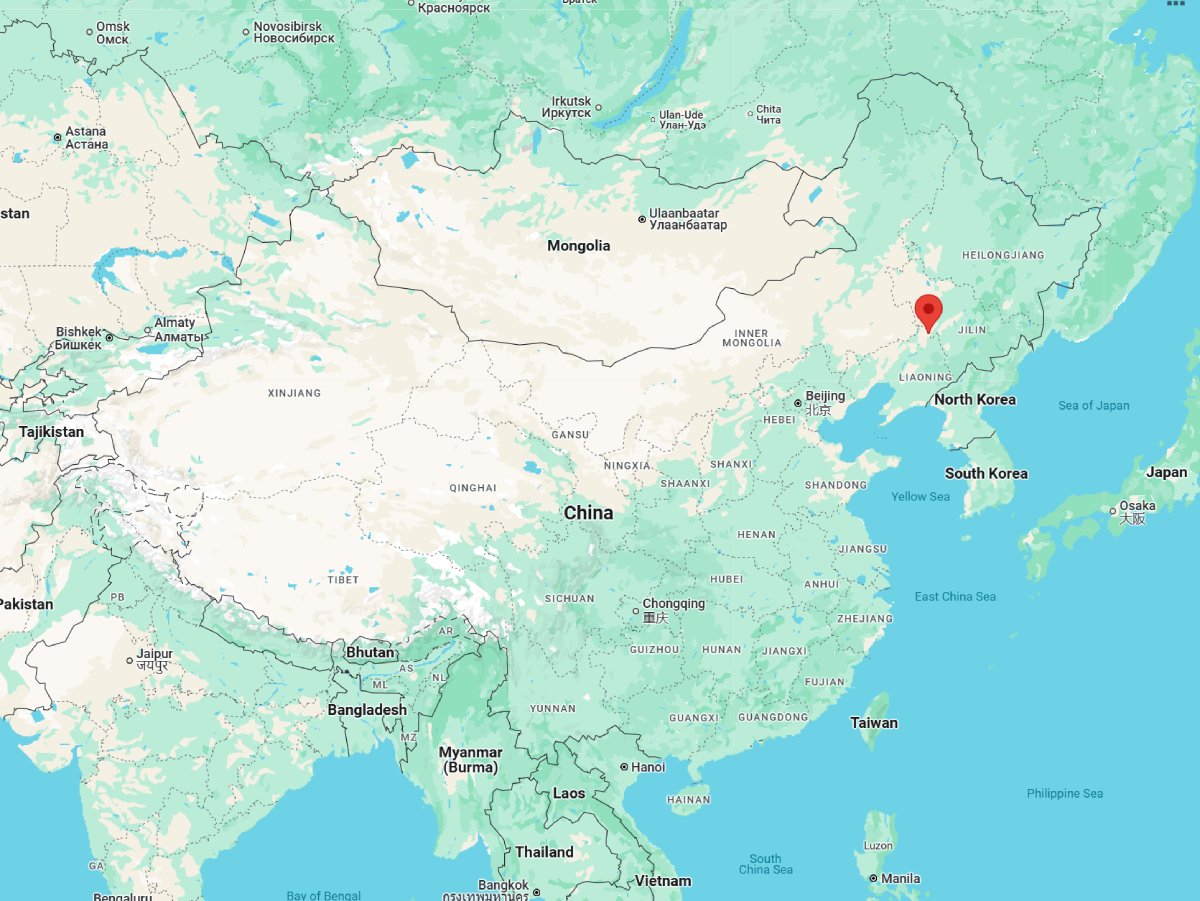

Life in Siping, Jilin Province (2014-2019)

The same is true for Siping, where I moved with my former Chinese husband and baby son after he was 100 days old.

In my experience, people in Kunming were generally friendlier toward foreigners than they were in Siping. I didn’t encounter much direct hostility, but people kept to themselves, didn’t tend to meet up with foreigners, didn’t make contact, weren’t interested in becoming friends, and didn’t want to be seen with them. I couldn’t make any friends with other parents in my son’s kindergarten classes because the other parents didn’t want to meet up with me. They had a lot of negative stereotypes about foreigners, and though not all of them were hostile toward me, they usually kept their distance. Only a few were willing to talk to me, but most encounters didn’t progress beyond a few brief exchanges. I also realized that locals in Siping weren’t as talkative as those in Shenzhen, for example, and generally kept to themselves more.

Siping is not an international city, and it is not a provincial capital, meaning there are fewer foreigners in the city. It has a few foreign teachers and exchange students (usually from South Korea or Russia). Free time is most commonly spent going to restaurants. Otherwise, there aren’t many activities. Siping has a few cafes and bars, but not many. Since I had a baby, and later a baby and a toddler, I wasn’t interested in going to bars anyway, but not being able to make friends with other parents was unfortunate. I don’t mind making friends with Chinese people, but Chinese people weren’t generally very accepting of foreigners in Siping. They thought I was somehow too different from them and weren’t usually willing to get to know expats, who they saw as inherently bad, with worse values than Chinese, sexually promiscuous, or viewed negatively in other ways.

I still managed to talk to a few Chinese people, even though the conversations, which used to be plentiful in Shenzhen, where many Chinese people liked to talk to me and share their stories, became much less frequent in Siping.

Here Are a Few Conversations I Had With People in Siping:

Even though I couldn’t make friends with locals, I still enjoyed being in Siping with my children, with whom I spent most of my time. If you’re a new mother, you’ll know that taking care of a baby is a lot of work, and meeting up with others is usually not a priority. However, it can still be comforting to spend time with others, and being isolated in a different country can lead to depression, feelings of loneliness, and generally make it harder to enjoy life. I was able to make friends with a few of the other foreign teachers working at Jilin Normal University, who lived in the same house as me.

In 2019, I left Siping for Germany.

I haven’t experienced Covid-19 in China, which I’m glad for (but if I could choose between experiencing Covid-19 in China and being with my children versus not experiencing it but not being with my children, I would choose the former, not the latter). I’ve heard many stories about how strict the lockdowns were in China and how hard it was for expats to live there during the pandemic with all the regulations, such as the health code. Many expats have left China since then because of these strict regulations, and some have left because schools and universities stopped hiring foreigners and resorted to online video classes instead. I probably wouldn’t have been able to stay in Siping even if I had stayed longer. The other teachers I knew had all left China for the US after the Covid-19 pandemic started, and the last time I inquired, the university was looking for foreign teachers willing to teach video classes from abroad but wasn’t hiring teachers to work locally. The phenomenon of foreigners leaving China during the Covid-19 pandemic is called the “China expat exodus.” It included expats who had lived in China for only a few years, as well as long-term expats who had made China their home for decades.

Have you ever lived in China? Did you like it?