Articles

jingkids international

Cultural Adjustment: Where Do You Draw The Line?

Where do you draw the boundary when cultural expectations interfere with personal beliefs?

29/06/2016

Ruth Silbermayr

Author

How much do you adjust in a culture different from your own to show your respect of local customs? How much cultural adjustment is enough, how much too much?

I came to China solo and without a child. Although I tried to adjust as much as I felt was possible – thinking that this was what was right – I didn’t think much about the question of cultural adjustment in the beginning. I had studied Chinese and tried to embrace local customs with open arms, naïvely putting myself into one or the other dangerous situation because I didn’t want to offend anyone on cultural terms and – not having grown up in this culture – had trouble distinguishing between the individual and the cultural.

One of these situations came about when I traveled around China with another Western woman in 2009. The day prior we had arrived in a remote rural town in Sichuan that boasted a single dusty road lined by a few wall-tiled houses. I can’t remember seeing a single female person on the two days we stayed in that town. The guesthouse we stayed at had a restaurant on the first floor. The restaurant had concrete floors and walls, was only dimly lit, and lacked any decoration. The plastic stools and tables featured faded colors we couldn’t identify and didn’t make the location any prettier.

When we sat down to take a look at the menu on our second day in town, the 50-year old male restaurant owner insisted on treating us to local barbecue. After all, we were rare foreign guests in this little town. He spoke heavy and unintelligible Sichuan-dialect and wrote part of the conversation down for us in Chinese characters so we’d be able to understand. When we agreed hesitantly and waited in the empty restaurant, he suddenly locked the front door and used the excuse of taking a photo together to try kissing us. We warded him off, sprinted to the back door leading to the stairwell and up the stairs to our room as fast as we could. Still panting from the sprint, we locked the room from inside and quickly moved any heavy furniture we could find in the sparsely furnished room behind the door. Although that guy came chasing after us and knocked on the door for what seemed like an eternity, this was fortunately the last time we ever saw him.

This situation was rather extreme and happened while traveling, but I have encountered other similar situations even while living in more metropolitan cities in China.

I met my Chinese husband at the end of 2012. We married and had a child. Our son is Chinese and Austrian and the question of cultural adjustment has gained much more significance now.

Thinking back, it all started when daye, my father-in-law’s oldest brother and the oldest patriarch of the Chinese family I married into, wanted me to raise my glass to him to show him, the oldest living male family member of the male family line, my respect. I was the youngest person at the table and should actively raise my glass to him, so the custom. He used the excuse that I have been here for a few years already and must therefore be accustomed to local rules. He had made it clear that he didn’t consider my husband married because although we were already legally married and had a wedding ceremony in Austria, we hadn’t had a ceremony in China (yet). When he asked me a few personal questions, he answered most of them for himself without waiting for my answers, assuming things about me he couldn’t possibly know. It started with simple things like food – his assumption being that steak and hamburgers are both staples in my home country – and the fact that we don’t generously share food with each other like Chinese people do, but all eat from our own plates.

He went on with lots of other questions about my age, education and more. When he asked me what I should call him (referring to the Chinese family relationship titles members of the family use to address each other), I told him that shushu (younger brother of father/-in-law) was the only title that I could remember meaning “uncle”. The correct answer would have been daye (oldest brother of father/-in-law), a word I didn’t yet know. Asking me one inquisitive question after the other, I could feel him getting angrier minute by minute.

All the other relatives told him to just drop it. But he didn’t. When he ordered me to raise my glass to him, I couldn’t do it. He felt that he was being disrespected, but so felt I. It was a lose-lose situation. I took one thing away from it: There are some things I’ll never be able to adjust to, like having to raise a glass of liquor to the oldest male family member upon his request, thereby ignoring the fact that he had just said some very hurtful things to me (like not accepting the fact that I am married to my husband).

Now with a child, there are even more things I can’t adjust to. Although I try to be respectful in most situations, I will not put my child at a risk or in a situation where his rights won’t be respected. He’s only two years old and as his parent, it’s my responsibility to protect him, culture or not.

In most situations I can be at ease and let him interact with friendly locals on his own terms. He’ll happily greet our compound’s fuwuyuan (service people) all dressed in black and white, whom he calls ayi (aunts), and often plays a little with them downstairs when we come back home from our normal afternoon walks. He’ll answer questions by curious strangers about his age and Chinese zodiac when we’re outside to play.

In some situations, I will interfere. Like when (usually) well-meaning strangers want to hug or kiss him. One day while sitting on a swing with my son, an elderly man with thick white hair came up to us and we had a friendly chat. When my son left the swing, the man realized it was because he needed to pee. He showed us the closest tree and waited there as though he wanted to watch. I took our son and ran with him as fast as I could to a little hidden place in the opposite direction where he could go without anyone watching.

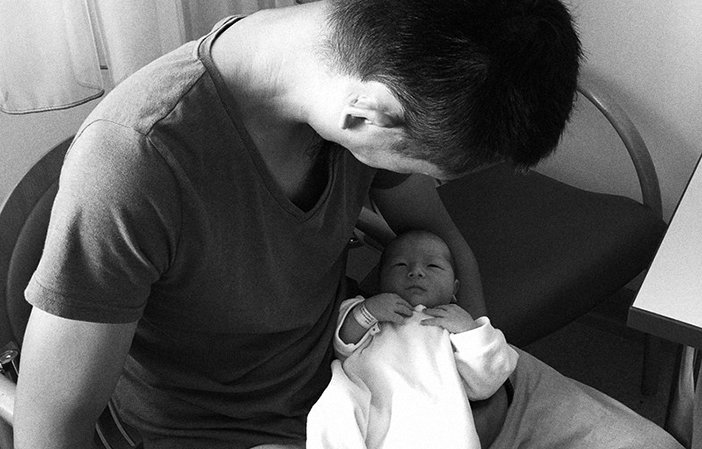

I’m not even very strict about these things compared to my husband. When our son was a baby, my husband would fiercely stop strangers from poking him in the face or touching his hands (both of which are very common here). He’d call strangers out if they stared at him a little too obviously or asked a few questions too many. He’d call them out in a humorous way, like asking if they were checking his hukou booklet, the Chinese residence booklet that includes information on births, marriages, divorces, moves, and deaths in a family. Once I called out a woman who began a sprint of over a hundred meters just to take a good close stare at the mixed baby in the stroller. I told her that my son is a human being, not a zoo animal. She verbally insulted me for saying so. That’s okay. Sometimes protecting our children is more important than giving someone face or keeping our own face.

My husband taught me that just because you’re Chinese doesn’t mean you’ll be okay with all of society’s or certain individuals’ rules. And just because you’re a foreigner doesn’t mean you have to adjust to cultural rules that make you really uncomfortable. Respect for other cultures is important, but so is respecting yourself, your own values and your children.

Where would you draw a boundary?