articles

China Elevator Stories

From Nazi Germany to Shanghai: The Struggle for Jewish Survival

During the Second World War, Shanghai was the only place in the world where Jews could enter without needing a visa.

03/10/2024

Ruth Silbermayr

Author

As could be seen in Ernest G. Heppner’s story of his emigration to Shanghai, Jews who wanted to leave Germany during Hitler’s reign had a hard time finding a country that would take them in. In his book A Study of Jewish Refugees in China (1933–1945): History, Theories and the Chinese Pattern, Guang Pan describes this situation:

“Facing the exodus of Jews from Europe, the world did not take positive action. Except for issuing some sympathetic statements, most countries just stood by and did nothing. (…) In 1938, a conference was held in Evian, France to discuss and address the problem of Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany. It was the hope of many that these countries could find a way to open their doors to allow more than their usual quotas of immigrants into their countries. Instead, although they commiserated with the plight of the Jews under the Nazis, every country but one refused to allow in more immigrants.”

As could be seen in the initial reactions of many countries to Ukraine’s plight for help, some countries acted similarly before or during the Second World War regarding help for the Jewish population. Guang Pan writes:

“Neutral countries like Switzerland and Sweden managed foreign affairs with great discretion for fear of offending Nazi Germany. As Hitler attached great importance to anti-Semitism in Germany’s national security strategy, any action in favor of Jews would be viewed as offense to Germany.”

He further explains:

“As a matter of fact, the complicated international situation in Europe and worldwide plus the concern of individual nations for their own interest deterred these countries from accepting a large number of refugees. (…) Some people suggested transporting all the Jews to Asian, African and Latin American countries, such as the Philippines, Madagascar, Kenya and Argentina. However, it did not work out well: first, these countries were poor and it would be extremely hard to raise enough money to build new shelters for the refugees there; secondly, refugees were unwilling to settle in such countries where living conditions were poor and the local culture was so different from the Jewish religion and national identity. In such a context, China, especially Shanghai, was the hands-down choice of the desperate Jews as their haven.”

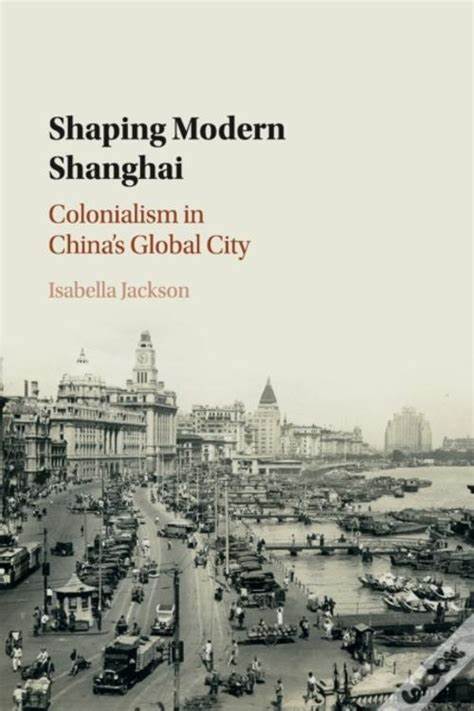

Today, Shanghai is China’s most international city, and unlike many other Chinese cities, Shanghai has a long history of featuring a foreign population. Colonialism through different foreign powers is part of Shanghai’s history, and its international character can still be seen in Shanghai’s architecture today. In Shaping Modern Shanghai: Colonialism in China’s Global City, Isabella Jackson describes Shanghai:

“The Bund is the most obvious physical legacy of the foreign influence on China’s most prosperous city. The buildings reflected the transnational colonial presence in Shanghai and China more widely: ‘transnational’ because it cut across and transcended national allegiances and was developed by non-state actors who moved between different parts of the world. The International Settlement that extended north and west from the Bund, encompassing 8.66 square miles at the centre of Shanghai, was a unique political entity that exemplified the peculiar form that colonialism took in China. It has been rightly recognized that the British were dominant economically and politically, but this has been assumed to mean that only British colonialism mattered. In fact, and increasingly, other colonial and transnational forces influenced how the Settlement developed, (…)”

Before the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe, China was facing its own problems. The Kuomintang (国民党 or Nationalist Party of China) ruled China from 1927 to 1949. The Chinese Civil War, marked by a fierce struggle for power between the Kuomintang and its opposing party, the Chinese Communist Party, lasted from 1927 to 1950. The Second Sino-Japanese War lasted from 1937 to 1945.

“The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part of World War II, and often regarded as the beginning of World War II in Asia. It was the largest Asian war in the 20th century and has been described as ‘the Asian Holocaust,’ in reference to the scale of Japanese war crimes against Chinese civilians. It is known in China as the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (抗日战争).

On 18 September 1931, the Japanese staged the Mukden incident, a false flag event fabricated to justify their invasion of Manchuria and establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo. This is sometimes marked as the beginning of the war. From 1931 to 1937, China and Japan engaged in skirmishes, including in Shanghai and in Northern China.”

Three provinces in China, Heilongjiang province, Jilin province, and Liaoning province were under Japanese occupation. Mukden was the Manchu name of Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province. Japan had also tried to occupy other areas in China. One major battle that was fought is known as the Battle of Shanghai, which happened in 1937, and led to the Japanese occupation of the city, which lasted until 1945.

When Jews had to leave Nazi Germany for Shanghai, they were facing a very uncertain future in China. Even though regional upheavals meant Shanghai wasn’t the safest option, the Chinese had generally been welcoming to Jews. This is how Guang Pan describes the relationship between the Chinese and the Jews:

“Chinese and Jews have gotten along very well in history. It had been nearly fifteen centuries since the first Jewish immigrant arrived in China and Jewish immigrants had been warmly engaged by their Chinese neighbors. For example, Jews in Kaifeng had even been assimilated and become indistinguishable from the local Chinese. In the 19th and early 20th century, when China’s door was forced open, more Jews poured into China, and Shanghai gathered the largest Jewish population in China. Most importantly, Jews have never met with anti-Semitism in China. In their mind’s eye, China was a friendly country. (…)

As China was forced to open its door in recent centuries, more Jews came to China and most of them settled in Hongkong, Shanghai, Harbin and Tianjin. Shanghai was a major destination for Jewish immigrants after 1840. (…) While the Jewish community in Shanghai grew, a new anti-Semitic tide surged in Europe, thus, creating a striking contrast: exclusion, persecution and slaughter in Europe versus inclusion, peace and prosperity in Shanghai.”

I was wondering if there were also foreign powers in China at that time who supported the Nazis and persecuted Jews in Shanghai or in other areas. Guang Pan explains the situation as follows:

“It is true that some Russians, Japanese, Nazis and the puppet regime of Manchuria controlled by the Japanese did organize anti-Semitic activities in Shanghai and Harbin, but such activities were ‘imported’ and had basically nothing to do with the local Chinese people.”

He further explains the Chinese population’s friendliness towards the Jews:

“The anti-Chinese atrocities over the past centuries bore a close resemblance to the anti-Semitic movement in Europe. Naturally, the Chinese were sympathetic with the Jews and strongly opposed to all forms of anti-Semitism.”

As was shared by Ernest G. Heppner, Jews didn’t need a visa to enter Shanghai. In A Study of Jewish Refugees in China (1933–1945): History, Theories and the Chinese Pattern, we find a further explanation as to why:

“After the August 13 Incident in 1937, the Japanese militarists occupied parts of Shanghai. (…) China could not continue to exercise its authority over the city because its government agencies had been evacuated. However, as the Japanese authorities had not yet established their puppet authority in Shanghai, Japan was unable to exercise overall and effective control over Shanghai, either. Those concessions were left out and open. No formalities were required for foreigners to enter Shanghai by sea.

Especially before September 1939, foreigners could enter Shanghai without visas and economic security, and they did not have to find a job in advance or submit any document like the certificate of morality issued by the police. Shanghai was the only city in the world where anyone could enter freely, which was important for Jews from the Nazi-controlled areas. Most of them had been ‘prisoners’ in concentration camps, mostly without visas, passports or money. Some of them were even ‘illegal’ immigrants. It was almost impossible for those Jews to enter countries requiring normal immigration procedures, let alone those strictly enforcing quota restriction on immigration.”

In 1943, this changed when all Jews in Shanghai were forced to live in the Shanghai Ghetto. Japan had begun collaborating with Germany regarding the Jews in Shanghai, and about 15,000 Jews were confined to an area of approximately one square mile, living in close proximity under poor sanitary conditions.

Have you ever read about this fascinating part of history?