articles

China Elevator Stories

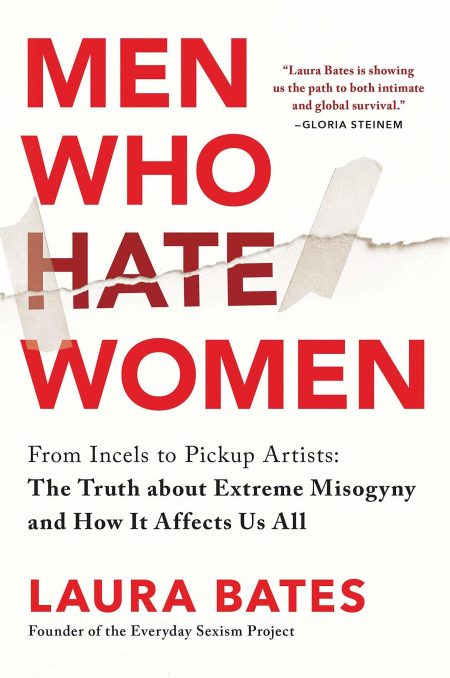

Men Who Hate Women - From Incels to Pickup Artists: The Truth about Extreme Misogyny and How It Affects Us All (by Laura Bates)

Many women have experienced harassment by misogynistic men.

xx/xx/2024

Ruth Silbermayr

Author

The book Men Who Hate Women – From Incels to Pickup Artists: The Truth about Extreme Misogyny and How it Affects Us All by Laura Bates is described as a broad, unflinching account of the deep currents of loathing toward women and anti-feminism that underpin our society and is a must-read for parents, educators, and anyone who believes in equality for women.

Just like Laura Bates, I used to believe extreme misogyny is a rare occurrence and not the norm. These past few years of living in Austria, I have had one experience after another with misogynistic men, and the number of them life has sent my way seems sheer endless.

Laura Bates explains the common misconception that misogynistic men are rare in her book:

“Perhaps you think there might be one or two men online with wild opinions and worrying views about women, but that’s just the internet – they’re just sad teenagers sitting in their parents’ basements, whiling away the hours in a pair of grubby Y-fronts, clutching a packet of Doritos under one arm. They don’t pose any real threat. They’re more to be pitied than feared.

Even the word we use to describe women-hating communities encapsulates this attitude perfectly. Beyond the occasional news report or small-circle conversations within feminist activist spheres, most of us do not know about the sprawling web of groups, belief systems, lifestyles, and cults that this book will unravel.

Those who do know it, describe it as the ‘manosphere’.”

Now, in the eyes of a few of my family members, the violence and threat my Chinese ex-husband poses, for example, don’t exist. In their eyes, I am the one who’s exaggerating. One sister tried to forbid me from applying for sole custody when I told her I had just done so. She also tried to suggest I was in the wrong for wanting to report my ex-husband to the police. I believe it may have been because she hadn’t found any severe signs or documents proving his abuse in the files I used in court and had saved as an extra copy on her hard drive, so I wouldn’t face the problem of losing all data again.

She portrayed herself as someone who knew more about my marriage and my ex-husband than I did. Not the one who experienced years of death threats, extreme rage, and an abusive marriage—who was therefore knowledgeable about what happened to her, understood the danger of the situation, and could decide how to react appropriately—was the authority on her own experience, but she was! This kind of behavior occurs frequently and can put a victim’s life in extreme danger when someone suggests that the victim is not knowledgeable about what she experienced and that another person is not dangerous and doesn’t pose a real threat.

Her behavior toward me also showed that she believed she had the right to raise her child while I wasn’t allowed the same privilege. In her eyes, my desire to apply for sole custody meant I was a bad person trying to steal my children from my ex-husband, who certainly wasn’t as bad a person or father as I was making him out to be. The sibling rivalry I experienced at her hands was severe; she bullied me out of the family with a few other relatives. Her cruel, callous behavior almost drove me to suicide.

Another sister didn’t answer my call for help when I asked her to send me a signed letter confirming the date of the first arson incident, so I could then use her letter to report both instances where my Chinese ex-husband had tried to kill me by committing arson to the police.

This was just one of many instances where I asked certain family members for help but received none. Imagine asking for help 1,000 times and only receiving it a handful of times because certain family members went behind your back, smeared your name, and portrayed you as a bad, flawed person.

Others have said my family members love me. What is love? Love is giving help when asked and when needed. What I have experienced does not fall into the category of “love”.

In this song, Namika asks, as a child who has experienced domestic violence at home, if the violence she is experiencing is all her fault.

What I have experienced is what often happens when one person is treated as the scapegoat in a family. The scapegoat typically isn’t different from the other family members but is treated differently and unfairly. Consider the story of Mother Hulda: she had two daughters—one was lazy, but was treated preferentially and could do no wrong, while the other, who was much more hardworking, was treated horribly and could do no right.

The scapegoat is usually completely innocent, but the one others point to as the instigator of problems, the one who did something completely wrong and evil, the person who is to blame, even when they aren’t at fault.

It also shows a bigger picture: that people don’t believe certain men are actually as bad and as violent as women make them out to be in their stories, because, after all, a story can simply be thought up. For sure, they had all met my ex-husband and seen that he seemed to be a decent human being who had conducted himself politely at public and family gatherings.

A Western woman who is married to a Chinese man, who wanted to stay anonymous because of the negative backlash she has experienced in the past when she shared her story, relayed similar stories to me—not about misogynistic men, but about discrimination, victim-blaming, and racism she had experienced. In her case, her experience was not because her husband is abusive—they are happily married and have been so for many years—but because of a situation where she and her husband experienced repeated discrimination. She writes:

“I understand not wanting to write about your story. I also experienced similar backlash; there were always people determined to blame us for what happened. Victim blaming, hand in hand with the ‘personal responsibility’ mantra that is wielded like a weapon in many cultures, is an easy way for people to explain away what happened while absolving the power structures and systems that were the agents of harm. Of course, a lot of people also buy into the idea that ‘good things happen to good people’ (and vice versa)—this is a lie, of course, but some people have internalized this fallacy.”

In this woman’s case, the discrimination she was experiencing took place both in the offline and online spheres, just as it did in my case.

In the offline sphere and in certain Western countries, certain people may not live in a group with other misogynistic men, but they spend most of their time in groups of misogynistic men in the online sphere. And even in the offline sphere, misogyny is becoming more common and widespread and can be seen in how women are treated in society. In Austria, women are treated abysmally. This problem is aggravated by a huge number of women who protect and enable these men.

In Laura Bates’s eyes,

“these are communities that exist largely online, the massive underbelly of the iceberg going largely unnoticed and unseen, yet the tip extends into our ‘real’ world and becomes sharper and bolder every day.

Perhaps you feel like we all need to calm down and remember that what happens online isn’t real life – sticks and stones might break your bones, and all that.

Maybe you’ve heard that freedom of speech is under threat, and if millennial snowflakes and PC warriors are allowed to have their way, nobody will ever be able to say anything critical about women or minority groups on the internet again. Or you might have heard that one of our vital freedoms is being undermined by pearl-clutching, humorless women taking offense at a few risqué jokes.

But what if there’s more to it than that? What if it’s almost impossible to get to grips with the epidemic of violence facing women and girls when we’re not able to clearly name and examine the problem? What if we can’t begin to take a comprehensive and effective approach to policing acts of violence because we don’t describe them in ways that acknowledge the connections between them? What if we are so inured to particular forms of violence that we consider them cultural, personal … inevitable? What if our ideas about men and women, about misogyny and hate crime, about what terrorists look like, are so trapped in stereotypes that we’re making terrible mistakes? What if those mistakes have devastating consequences?”

In my case, I have observed that people were unwilling to help. What does this mean? It means that people generally felt better when they could see me suffer. This is completely abnormal behavior, in my mind, but it is what I have had to endure over and over, and I don’t see this changing anytime soon. In the case of misogynistic men, it also means that women who need help don’t receive the necessary support.

When people don’t face these problems head-on and they are only considered single instances of violence, and not seen as a mass phenomenon—and because civil courage is basically non-existent in our society—this also means that we won’t be able to reverse these trends.

Laura Bates, who has experienced misogynistic online attacks, further writes:

“Why are these men so angry? Why do they hate me so much? Because I started a little website called the Everyday Sexism Project through which people (of any gender) can share their experiences of sexism and inequality. I asked people to talk about their stories and I gave them a space to do so. And that innocuous, simple act in 2012 was enough to unleash a torrent of abuse that continues to this day, spiking and redoubling every time I discuss the project online or in the media. It follows me to speaking events, where angry men hand out fliers to calling me a liar, or into bookstores, where they leave handwritten notes in my books, warning readers that women lie about rape.”

I have found that these lies are common nowadays. From my own observation, these now grown-up men were parented by men who taught them to hate women because they hated their own wives, ex-wives, mothers, or other women in their lives.

But these movements haven’t always been as extreme.

I remember that the internet and the general population used to be much more relaxed, nice, and helpful in the past. Of those men who have attacked me horrifically simply because I am a woman, 100% were malignant narcissists. In my experience, narcissistic men are often misogynistic and hate women. Because they perceive themselves to be the victims, not the perpetrators, they also see themselves as the victims of women.

In my case, it all started when I moved back to Europe in 2019. Before this, I was rarely attacked, and when I was, these attacks were singular instances, not worth mentioning. But in 2019, these issues really came to the surface. I believe this reflects a change in society, one that was certainly underway before 2019, but has become more obvious in the past few years. Before this, what I was observing was more covert misogyny and sexism, but after 2019, the misogyny and sexism became blatant, and men didn’t hold back from attacking me like they used to.

To me, this shows that there were processes that enabled these men to be blatantly aggressive, violent and misogynistic in public; processes that were somewhat new, because these same men had hidden their aggression towards me in the past.

I often wondered what the real cause was, but I believe it must have been partly related to my blogging career. The process of people aggressively attacking others for having their own opinions or for being different (in their minds), along with large-scale bullying, began with the COVID-19 pandemic, if not earlier. In my case, I frequently asked myself what it was that drove people to harass me. Was it because I had found some success with my blog? Was it because I had a story published in an anthology? Was it because I now had two children?

The first two reasons I have observed are certainly part of why people react differently to me. Many, including successful men, envy my success. Not that there’s anything to envy here.

I have watched sexist men in the generation before ours, but I haven’t observed there were as many aggressive and violent misogynistic men roaming the streets, attacking women wildly without any real reason. Nowadays, it’s all I’m dealing with all day long.

I have also encountered a large number of men who believed I had no right to my children. Why so many people think that children shouldn’t be raised by their mother remains a mystery to me.

In Laura Bates’s case, she was determined to get to the root cause of what was really going on with society. She writes:

“So, over the period of a year, I immersed myself in these communities to find out how all of this is happening, and to expose a powerful, hate-fueled force that is currently underestimated by the few who know about it, while remaining invisible to everybody else altogether. I wanted to lay bare the reality of a hate-movement, the very existence of which we have completely failed to acknowledge, and ask: what is attracting men and boys to this ideology? How does it spread?”

She shares:

“Almost every week for the past eight years in a row, I have spoken to young people in schools across the UK about sexism. But, over the past two years, boys’ responses started changing. They were angry, resistant to the very idea of a conversation about sexism. Men themselves were the real victims, they’d tell me, in a society where political correctness has gone mad, white men are persecuted, and so many women lie about rape.”

Have you also observed this trend toward a more misogynistic society?